Article

Chronic non-cancer pain is an expensive and growing problem within

industrialised countries. In a 1998 review, the

Marinker (1998), in a discussion of concordance versus compliance,

cited studies indicating that when there is congruence between service

providers’ and service users’ beliefs about treatment, concordance is higher.

Patient concordance with treatment is inextricably connected with the

individual’s perception of whether the intervention is relevant, meaningful and

likely to be successful (Kotarba and Seidel 1984, Donovan and Blake 1992,

Schussler 1992, Yardley and Furnham 1999). The treatment endorsement patterns

of both service providers, like occupational therapists, and service users need to be identified and compared.

Participants in the study attributed a range of negative effects

to physicians’ disbelief of their pain. These effects included: growing

self-doubt, increasingly unsupportive family members, inaccurate information

going to employers, frustration over feeling that the physicians did not listen

to them, and the perception that physicians disbelieved their pain. Eccleston

et al (1997) compared a composite group of 60 physicians’ and patients’

understandings of the causes of chronic pain. This study revealed that while

common categories of belief emerged (blame, responsibility and the need to

protect identity), the two groups did not share common beliefs within those

classifications.

Aim of the study

The Pain Society (British and Irish Chapter of the International

Association for the Study of Pain) identified occupational therapists as important

members of the treatment team in its report, Desirable Criteria for Pain Management Programmes (Pain Society 1997). It follows that the issues discussed above

are of relevance to occupational therapy and require closer examination. This

paper presents the occupational therapist findings that have been extracted from

the results of an ongoing much larger multidisciplinary study, examining

service providers’ and service users’ congruence of beliefs regarding specific treatments for chronic

pain.

The literature and websites related to chronic pain intervention

were reviewed and all the identified treatment components were listed. The

resultant list of 63 treatment components formed the basis of a questionnaire

(see Table 1 for the items included). This list was presented in random order

within the questionnaire so that respondents would not be influenced by

researcher-identified categories. The questionnaire section of interest in this

report asked respondents to identify which treatment components they personally

endorsed as needed or not needed for people withchronic pain.

Participants and procedure

The board of the National Occupational Therapy Pain Association

gave its permission to survey the membership (93 therapists at the time of the

study) and provided mailing labels. The members were informed in the covering

letter that return of the questionnaire would be taken as consent to

participate. The participants were also invited to volunteer for a follow-up

phase of the larger research project and requested to provide contact

information if they were interested. Because of this, in eight cases it was

possible to return questionnaires to participants for additional information

where sections had been omitted or misunderstood.

Findings

Of the 93 questionnaires, 44 (47.3%) were returned. There were 41

women and 3 men, whose ages ranged between 28 and 60 years (mean = 41 years)

and years in practice between 1 and 31 years (mean =14 years). The most commonly

reported type of pain-related work was with mixed caseloads (n = 33, 75%), followed by work with people having

pain related to orthopaedic conditions (n = 8, 18.2%). The respondents showed a

wide range in hours of undergraduate training, with 34 (77.3%) reporting that

they had received 0 hours of training in pain and pain management. Only 3 (6.8%) of the total group had received more

than 15 hours of pain education as undergraduates. At a continuing professional

development (CPD) level, although 7 (15.9%) therapists reported having only 10 hours

or less of additional training, 29 (65.9%) had participated in over 30 hours of

pain-related CPD.

Organising therapists’ beliefs about treatment components

The range of treatment components that therapists ranked as needed

or not needed was grouped into five general categories: (A) Education for

self-management, (B) Health care professional applied biomedical interventions,

(C) Health care professional applied psychosocial interventions, (D)

Facilitation of peer-support network and (E) Complementary therapies. A panel

of occupational therapy lecturers at the

BPCQ scores

The respondents reported higher rates of endorsement for beliefs

around internal (IS) factors as influencing pain, followed by chance happening

(CH) and an overall low belief in powerful doctors (PD). In comparison with Skevington’s

(1990) findings for these subscales with nonpatients, marked differences are

evident in the PD and CH scores (Table 2). Because Skevington’s (1990) figures

are not normative, the two groups can only be compared for the purpose of

provoking discussion; no statistically significant relationship is implied.

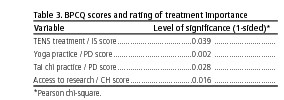

BPCQ scores were divided into categories of ‘high’ and ‘low’, with the mean score used as the divide for ranking. Chisquare analysis of the high/low BPCQ scores and therapists’ beliefs that each individual treatment component was needed or not needed served to highlight several interesting trends. Statistically significant findings, as detailed in Table 3, emerged for the treatment components of TENS (transcutaneous electrical neuromuscular stimulation), yoga, tai chi and client access to research findings. Therapists who scored high on the IS (internal factors) scale in the BPCQ tended to see the use of TENS as a needed treatment for chronic pain (p = 0.039). Therapists who scored high in PD (powerful doctor) tended to believe that the yoga (p = 0.002) and tai chi (p = 0.028) treatment options were needed. The analysis also revealed that therapists who scored high on CH (chance happening) were more likely to endorse that people with pain needed access to research findings (p = 0.016).

Study limitations

There are several key limitations to the findings presented. Only 44

of the possible 93 (47.3%) questionnaires were returned, so the sample is less

than ideal and no claims of representativeness should be inferred. Because the

respondents could choose to be anonymous and there were financial restraints,

no follow-up of non-respondents could be carried out. Therefore, it was not

possible to determine demographic characteristics that might have influenced

participation in the study. Also, the respondents, because of their membership

in the National Occupational Therapy Pain Association, should be viewed as a

sub-specialty group of occupational therapists that may have a wider knowledge and

experience base in chronic pain than other occupational therapists.

Lastly, survey data do not capture the full range of responses

possible in exploring a complex area such as pain. This postal survey focused

on ‘what’ occupational therapists endorse and provided predominately

quantitative data. However, without a follow-up examination of ‘why’ the therapists held these preferences, interpretation can only be

incomplete and speculative at best. The second, qualitative stage of this

research is currently being designed.

Discussion and conclusion

This survey has provided a preliminary profile of a group of

occupational therapists’ beliefs in relation to chronic pain treatments. There

was a wide range in respondents’ years of experience and hours of CPD training

related to chronic pain. Most of the therapists worked with clients from a

mixture of diagnostic groups, and nearly 75% of all the therapists

participating in this study had received no dedicated training on pain during

their undergraduate education. The study

respondents appeared to be a heterogeneous group of therapists, each

bringing a unique blend of training and experience to his or her practice. This lack

of consistency was mirrored in what individual therapists felt were necessary

treatments for chronic pain, although a definite trend was evident in the

categories of treatment that the therapists tended to endorse more uniformly.

The therapeutic interventions related to Education for self-management were found to be more consistently identified as needed for treatment. It is possible that this is partially a function of the high amount of CPD that the therapists engaged in. Also, this may be related to the profession’s core philosophy of enabling occupation. According to Law (1997, p2), ‘enabling occupation means collaborating with people to choose, organise and perform occupations which people find useful or meaningful in a given environment’. Self-management approaches to chronic pain are evidently one such enabling tool that occupational therapists are well prepared to facilitate.

A potential explanation for another of the study’s findings may lie in the combination of this focus on enabling, the profession’s philosophical roots of client-centredness (Law and Baptiste 1995, Sumsion 2000) and the concept of occupational competence (Matheson and Bohr 1997). The BPCQ scores reflected that the National Occupational Therapy Pain Association group of occupational therapists tended to believe less strongly in the idea of a ‘powerful doctor’ (or other health care professional) and in ‘chance happening’ than non-patients from other studies (Skevington 1990). Occupational therapists ascribe to a belief system that people have mastery in their own lives and are not controlled by random fates.

The study produced some less easily understood findings,

particularly in light of the above-mentioned beliefs. As identified, there was

a positive relationship between high BPCQ scores in the ‘powerful doctor’ (PD)

category and endorsement of yoga (p = 0.002) and tai chi (p = 0.028). While it may be argued that it is in keeping with occupational

therapists’ philosophy of client-centredness to support lifestyle choices for

complementary therapies (such as tai chi and yoga), it was puzzling that this

endorsement was found within the subgroup of respondents (31.8%) who scored high in their belief in ‘powerful doctors’. Although the

majority of respondents did not strongly endorse ‘powerful doctors’, the

findings seem to suggest that there may be a subgroup of therapists that is

supportive of alternative interventions focusing on a client-centred definition

of ‘useful’, while at the same time still operating within a medical model

endorsing the concept of professional expertise.

Two features of current health care may offer some insight into

this apparent contradiction. First, most occupational therapists, as

demonstrated in the findings of this and other studies (Scudds and Solomon

1995, Unruh 1995, Rochman 1998, Strong et al 1999), have a paucity of

undergraduate education and training in pain. This may leave them poorly

equipped to formulate an evidence-based argument for the pain interventions

that they provide and/or endorse. Although the therapists did report a high

rate of CPD in chronic pain, this expertise is acquired over time.

The question of whether practice and beliefs change with CPD is

only now beginning to be addressed within the discipline (Jones et al 2000).

Often working within large hospital-based services and multidisciplinary teams,

therapists may adopt the values of other team members whose professional

underpinnings and treatment approaches are theoretically grounded in biomedical

reductionism (Freeman et al 2000). In this scenario, it would be possible to

see an occupational therapist as swaying between the influences of the

team milieu and his or her professional tenets.

A second consideration in exploring these unexpected findings is

that health care practitioners are subject to the social forces in which the

health care service is provided. Recently, Weinblatt and Avrech-Bar (2001)

challenged occupational therapists to develop a questioning attitude towards what they traditionally hold to be ‘truths’ about science

and medicine. They proposed that occupational therapists need to understand how

postmodernism challenges commonly held modernist beliefs that health care consists

of universal truths and principles explained through scientific analysis. In postmodernist thinking, there are no universal

givens and personal reality changes in relation to the sociopolitical, temporal

and environmental contexts in which an individual lives (Siahpush 1998). The

emerging social phenomenon in western cultures of challenging biomedicine’s

superiority has seen a growing exploration and endorsement of interventions

that previously were held to be from the fringe and ‘alternative’ (Hodgkin

1996, Raithatha 1997, Siahpush 1998). The findings of this study, where

50%-79% of occupational therapists stated that they believed interventions such

as acupuncture, yoga and meditation to be needed for the treatment of chronic

pain, lend some degree of support to this idea.

Weinblatt and Avrech-Bar (2001) emphasised that occupational therapy is well positioned to offer interventions from within both traditional science driven models (such as biomechanics and exercise physiology) and methods that reflect a postmodern redefinition of health based on individual perceptions, beliefs and values. The profession’s client-centred philosophy allows occupational therapists to work flexibly with a variety of clients, each of whom defines his or her own ‘truth’. The findings of this survey, where therapists support traditional biomedical constructs at the same time as endorsing ‘alternative’ interventions (such as yoga), may cautiously be interpreted as lending support to Weinblatt and Avrech-Bar’s (2001) proposition. As discussed above, this survey only examined the ‘what’ of occupational therapists’ beliefs. Stronger evidence-based interpretation cannot go forward until the ‘why ‘ is added to the equation. Occupational therapy is only beginning to deal with the philosophical issues of constructivism and postmodernism and this paper makes no claims related to either paradigm. The introduction of these terms should be seen rather as a provocation, to stimulate and perhaps even aggravate the reader into further discourse.

Much more research is obviously needed. A qualitative second stage

to this study is now in development to explore what explanation occupational

therapists themselves bring to their decision making about chronic pain

interventions. Chronic pain is a complex and life-altering condition. Occupational

therapists, by virtue of their unique philosophical background, have much to

offer to people with chronic pain. The challenge now is for occupational therapists

to be willing to explore their own beliefs and attitudes while they seek a

shared understanding of pain and treatment interventions with the clients that they serve.

Acknowledgements

This study would not have been possible without the financial

support of the Constance Owens Trust; the willing participants from the

National Occupational Therapy Pain Association members; my research

supervisors, Professor A Jacoby (Department of Primary Care, University of

Liverpool) and Dr G Baker (Walton Neurological Centre); Dr Maria Leitner

(Director of Research, School of Health Sciences, University of Liverpool); and

my academic colleagues’ supportive but critical perspectives. My particular appreciation

to the thoughtful comments and guidance of the anonymous BJOT reviewers.

Thank you all

References

Bates MS, Rankin-Hill L, Sanchez-Ayendez M (1997) The effects of

the cultural context of health care on treatment of and

response to chronic pain and illness. Social Science and Medicine, 45, 1433-47.

Chapman SL, Jamison RN, Sanders S (1996) Treatment helpfulness questionnaire:

a measurement of patient satisfaction with

treatment modalities provided in chronic pain management programmes. Pain,68,

349-61.

Donovan J,

Donovan MI, Evers K, Jacobs P (1999) When there is no benchmark: designing

a primary care-based chronic pain management

programme from the scientific basis up. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management,

18(1), 38-48.

Eccleston C, Williams AC, Stainton Rogers W (1997) Patients’ and professionals’

understandings of the causes of chronic pain:

blame, responsibility and identity protection. Social Science and Medicine, 45(5), 699-709.

Fields HL (1995) Core curriculum for professional education in pain: a report of

the Task Force on Professional Education

of the International Association for the Study of Pain.

Freeman M,Miller C, Ross N (2000) The impact of individual

philosophies of teamwork on multi-professional practice and the

implications for education. Journal

of Interprofessional Care, 14(3), 237-47.

Hodgkin P (1996) Medicine, postmodernism and the end of certainty.

British Medical

Journal, 313(7072), 568-69.

Jones D, Ravey J, Steedman W (2000) Developing a measure of beliefs

and attitudes about chronic non-malignant pain: a pilot

study of occupational therapists. Occupational Therapy International, 7(4), 232-45.

Kotarba JA, Seidel JV (1984) Managing the problem pain patient: compliance

or social control? Social Science

and Medicine, 19, 1393-1400.

Law M (1997) Core concepts in occupational therapy. In: E

Townsend, ed. Enabling occupation: an occupational

therapy perspective.

Law M, Baptiste S (1995) Client-centred practice: what is it and

does it make a difference? Canadian

Journal of

Occupational Therapy, 62, 250-57.

LeFort SM, Gray-Donald K, Rowat KM, Jeans ME (1998) Randomised controlled

trial of a community-based psychoeducation programme

for the self-management of chronic pain. Pain, 74(2-3), 297-306.4

Maniadakis N, Gray A (2000) The economic burden of back pain in

the

Marinker M (1998) Compliance is not all. British Medical Journal, 316(7125), 150-51.

McQuay HJ, Moore RA, Eccleston C, Morley S,Williams AC (1997) Systematic

review of outpatient services for chronic pain

control. Health Technology

Assessment, 1(6), 1-135.

Pain Society (1997) Desirable criteria for pain management programmes.

Raithatha N (1997) Medicine, postmodernism and the end of certainty.

Postmodern philosophy offers a more appropriate system

for medicine. British Medical Journal,

314(7086), 1044.

Rathbun CR, Slate JR (1995) Lack of comparability of two pain

locus of control measures. Assessment

in Rehabilitation

and Exceptionality, 2(3), 153-61.

Rochman DL (1998) Students’ knowledge of pain: a survey of four schools. Occupational Therapy International, 5(2), 140-54.

Rochman DL, Herbert P (1999) Rehabilitation professionals’ knowledge and attitudes survey

regarding pain.

Schussler G (1992) Coping strategies and individual meanings of

illness. Social Science and

Medicine, 34(4), 427-32.

Scudds R, Solomon P (1995) Pain and its management: a new pain curriculum

for occupational therapists and physical

therapists. Physiotherapy

Seers K, Friedli K (1996) The patients’ experiences of their

chronic non-malignant pain. Journal

of Advanced Nursing,

24, 1160-68.

Siahpush S (1998) Postmodern values, dissatisfaction with

conventional medicine and popularity of alternative therapies. Journal of Sociology, 34(1), 58-70.

Skevington SM (1990) A standardised scale to measure beliefs about

pain control (BPCQ): a preliminary study. Psychology and Health, 4, 221-32.

Spence A (1999) Services

for people with pain.

Strong J, Tooth L, Unruh A (1999) Knowledge about pain among newly

graduated occupational therapists: relevance for curriculum

development. Canadian Journal of

Occupational Therapy, 66(5), 221-28.

Sumsion T (2000) Client-centred practice: the challenge of

reality. OT Now, July/August, 22-23.

Turk DC (1996) Biopsychosocial perspectives on chronic pain. In:

RJ

Turnquist K, Engel J (1994) Occupational therapists’ experience

and knowledge of pain in children. Physical and

Occupational Therapy in Pediatrics, 14, 35-51.

Unruh A (1995) Teaching student occupational therapists about

pain: a course evaluation. Canadian

Journal of

Occupational Therapy, 62(1), 30-36.

Von Korff M, Moore J, Lorig K, Cherkin DC, Saunders K, Gonzalez

VM, Laurent D, Rutter C, Comite F(1998) A randomised

trial of a layperson led self-management group intervention for back pain

patients in primary care. Spine, 23(23), 2608-15.

Vrancken MA (1989) Schools of thought on pain. Social Science and Medicine, 29(3), 435-44.

Weinblatt N, Avrech-Bar M (2001) Postmodernism and its application

to the field of occupational therapy. Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy,

68(3), 164-70.

Yardley L, Furnham A (1999) Attitudes of medical and non-medical students

toward orthodox and complementary

therapies: is scientific evidence taken into account? Journal of Alternative and Complementary

Medicine, 5(3), 293-95.

Author

Cary A Brown, MA, OTM(C), SROT, Lecturer, Division of Occupational

Therapy, University of Liverpool, Johnston Building, Brownlow Hill, Liverpool

L69 3GB.